LOW CARBON INFRASTRUCTURE: THE ROAD TO REDEMPTION

During COVID, as we literally turned off the ignition of the world, it was shovel ready infrastructure projects which topped government global agendas. ‘Connectivity’ drives growth and trade, which can be delivered in an almost ethereal sense, through the digital connections brought by sub sea cables, as well as physically through improving road networks.

Every year the EU alone produces around 15 million tonnes of bitumen. Most of this is mixed with aggregates such as crushed rocks and gravel to create asphalt – the sticky bitumen that binds it all together to build roads. Around 90 per cent of all roads are constructed using asphalt and essentially all of it uses bitumen as a binder. Whilst some bitumen does occur naturally, it is essentially a by-product of ‘boiling oil’ in a traditional refinery.

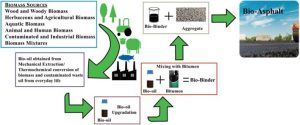

In Holland, they have made inroads into a substitute binder, bio-bitumen, using lignin as a natural adhesive. Wageningen Food & Bio based Research have built 8 demonstration roads, each with four years’ experience using 50% bitumen and 50% lignin, from different sources, such as paper pulp production and a bio refinery that produces cellulosic ethanol from straw. However, there are countless examples globally now of bio-bitumen surfaced roads building a durable and reliable track record, India has built over 60,000 miles of them so far over a two decade period. Ghana, a country that manages to recycle less than 5% of its plastics and has only 23% of its roads paved, has also determined to reduce the disastrous effect of enduring plastic bags. Nelplast, a Ghanaian company produces pavement blocks by shredding plastic and mixing with sand.

Aston university in the UK developed a process to break down the organic part of household wastes, plastic, paper and textiles, to product a sticky, glutinous substance similar to bitumen. Millions of tonnes of bitumen are consumed annually in road construction, although little of it is sustainable. Bio-bitumen in essence is created by heating the wastes to around 500 degrees in the absence of oxygen – again the process of pyrolysis discussed above. By changing the processing parameters, such as temperature, processing time and the product collection strategy, it is possible to refine the properties of the final bituminous type product.

There’s a wealth of research focussed on improving bitumen’s properties as a binder in road surfacing, and by extension the sustainability of roads. Polymeric materials are the staple additives used to make hot bituminous mixtures more flexible at low temperatures and more rigid at hotter temperatures. SBS (Styrene-Butadiene-Syrene) is the most used additive, but given the cost and fossil fuel derived nature of the polymeric additives, a host of creditable alternatives have been investigated – carbon based substances such as bio-oils, biochar, activated carbon, natural wastes, gum, poly saccharides and natural rubber. The chemistry varies however depending on the availability of feedstock in a given jurisdiction where bio-bitumen is being produced, there may be more than one silver bullet. Inter alia, plastics have perhaps attracted the most attention and represent one of the most promising modifier of all the bitumen modifiers.

However, we shouldn’t ignore the degree to which roads are already ‘recycled’. Besides the search for new bitumen additives, there is also the ability to put alternative binders to act as rejuvenators for aged asphalt, a prime example of a circular economy in action, which when reusing materials such as tyres for example, creates a closed loop system which is demonstrably sustainable and a low carbon infrastructure. The roads are usually quieter too.

Using plastics in road construction has raised questions over the environment issues surrounding melting materials such as PET, ( polyethylene terephthalate), the material used for the casing which holds carbonated drinks bottles. Fortunately, heating plastic does not create any further emissions, given that it requires temperatures of over 360 degrees for plastics to be at their gassiest. Before that, gentler heating up to 170 degrees is sufficient to move from solids to liquid, and therefore falls short of becoming a gas. MacRebur, a UK company which produces pelletised plastics and sold to construction companies globally, calculates that for every ton of bitumen left out of asphalt, as much as a ton in CO2 emissions is saved, since less petroleum is heated for bitumen’s extraction. Our own bio-bitumen laboratories continue to research new binding agents to reduce the carbon footprint of road paving whilst continuing to improve the durability of the material.