Manufacturing accounts for 29% of global emissions and affords one of the most stubborn of emissions stains. Not all clean tech climate solutions describe greenfield breakthrough technologies, some of the most significant gains can be made by retrofitting existing facilities. For example, we now have the means to inject waste carbon into fresh concrete, the end product that cement is used for – and as the second most consumed material on earth, unsurprisingly is one of the biggest emitters – accounting for 8% globally.

For example, Ecocem’s ACT Technology produces low carbon cement and has been approved by the EU for use across the continent, whilst being involved in the construction of the Athlete’s village for the Paris Summer Olympics. However, for over 50 years manufacturing has been anything but a one way street. A linear approach describes raw materials going in and finished products leaving from the other end of the production line. Post product warranties, manufacturers have scant further involvement. During that half century, the world’s consumption of raw materials has increased four fold, to nearly 100bn tonnes, according to the consultancy group Circle Economy. Unfortunately, as we stand less than 9% of this consumption is drawn upon again, discarded without further use. Circular manufacturing breaks with convention and does so with an eye to the bottom line.

Car manufacturing is an example which has circular manufacturing processes. Electric vehicles have become an everyday reality, although there remains the thorny issue of their batteries which rely on extractive metals that are difficult to source sustainably and limited by definition. Battery recycling becomes a cornerstone of the energy transition, whereby new batteries are produced, using up to 70% less emissions, refining the recycling existing units.

Moreover, batteries are the most expensive component in EV’s, and hence there is significant value in domestic production. Given the expense associated with procuring metals such as nickel, manganese and cobalt, common sense dictates that recovering and reusing them should be a profitable enterprise. In fact, Renault anticipate that ultimately 50-70% of cars can be recycled.

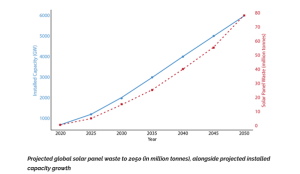

However, e-waste is accentuated by renewables technology. The first generation of solar panels is approaching the end of its life. With it comes a problem long ignored: mountains of photovoltaic (PV) waste. The International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) forecasts that 1.7–8m tonnes of PV modules will be discarded by 2030, rising to 60–78m tonnes by 2050, as early-adopter markets—China, the EU, the US, Japan and India—replace ageing arrays in bulk. The pace of disposal may accelerate further, driven by falling panel prices, storm damage or the odd hailstorm.

The strain is already evident. In Queensland, Australia, roughly 1.2m panels are scrapped each year. A local recycler currently processes 30,000 units annually; it hopes to expand eightfold, still a small fraction of the expected tide. In the absence of national stewardship schemes, most discarded panels will end up in landfill, except in jurisdictions that explicitly prohibit it. Europe has taken a different approach, folding PV modules into the WEEE (Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment) directive, which obliges producers to fund take-back schemes. The resulting patchwork of rules helps explain why recycling capacity trails the impending surge of waste.

Small-scale solutions offer limited relief. Microgrids—from Kenyan farms to German utility-scale installations—do not escape the waste problem. Redeploying panels for “second-life” applications can extend their usefulness, but the ultimate disposal challenge remains. Lifecycle studies confirm that PV microgrids outperform diesel generators environmentally, but they do not eliminate the eventual need to process spent modules.

Technology and capacity are improving, albeit from a low base. First Solar operates closed-loop recycling for thin-film panels, while European firms such as ROSI and PV CYCLE recover higher-value materials including silver, copper and high-purity silicon. In the United States, We Recycle Solar navigates a complex tangle of state regulations; California treats PV panels as “universal waste,” simplifying collection but complicating downstream processing. The aim is to move beyond merely reclaiming glass and aluminium to capture the elements that make recycling economically viable.

Africa is beginning to stir. South Africa has forged partnerships to develop PV recycling under new extended producer-responsibility rules, though continental infrastructure remains nascent even as volumes rise. Globally, the solution is clear: producer-funded collection schemes, harmonised regulations to attract investment in high-recovery facilities, and standards that reward circular content in new panels. Without such measures, the solar industry risks wasting the very materials it will need to sustain its growth. Navigate has already joined the cause. Targeting completion Q1 2026, Dar Es Salaam should boast a significant new recycling facility, one that will both act as a repository for regional PV panel waste, and also go somewhere to brighten the dark side of solar.