The very seeds which we sow and then how we proceed to cultivate them, has a major bearing on our climate. However, commercially viable synthetic fertilizers are one example of agricultural innovation, as opposed to those derived from hydrocarbons. By employing microbial products which draw nitrogen from the air, we can lessen impact by employing more efficient fertilizers, which need 1,000x less water and are responsible for less than 1% of the emissions of their conventional counterparts.

Moreover, there are other fertiliser solutions that are perhaps more mundane, yet yield significant climate benefits – products such as biochar. In many respects biochar, essentially rebranded charcoal, has lost its lustre. Ever since Abraham Darby, an English Ironmaker, happened upon ‘coke’ as an alternative to charcoal as the feedstock used to reduce his ore to metal, biochar began to lose its way somewhat. Less fortuitously, this switch of industrial feedstock paved the way for the steel making industry to become carbon emitting culprit number one. Ironically, biochar, may yet have a substantial decarbonisation role to play in redressing the balance and restore some of its former glory. There are various ways of producing biochar, each determined by a different feedstock, but it has a long history as a highly effective fertiliser, carbon store and fuel.

Biochar is no newfangled concept. Over a century ago, Herbert Smith exploring the deeper reaches of the Amazon, noted patches of ‘black earth’, notably more fertile than surrounding soils. It would appear that for centuries Amazonian Indians, burnt crops and deliberately mixed them with soil to enhance the yields. Modern practice bears this out – David Laird, of America’s Department of Agriculture, demonstrated some of the miracle properties of biochar in reducing the leaching of nutrients, (nitrate, phosphate and potassium), from mid-Western soils. The Maine based International Biochar Initiative pointed to peerless Colombian crops grown using biochar made from corn stower (a post corn harvesting residue). This is not to mention the how biochar also can remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

Pyrolysis described a process of passing materials through very high temperatures in the absence of air, or with very low oxygen. Using biomass as the subject matter, for example plants (that have absorbed Co2 as they grow during the quotidien carbon cycle taught through primary schools the world over), the combustive process produces charcoal, which elementally is predominantly carbon. When combined into soil, it is also hand brake on methane and nitrous oxide emissions, as it acts as a catalyst to decompose these gases.

In this respect, pyrolysis as a thermochemical process is emerging as a cornerstone of sustainable agriculture. By subjecting agricultural residues—such as rice husks, corn cobs, and sugarcane bagasse, to controlled heating, pyrolysis yields biochar, a carbon-rich solid that enhances soil fertility and water retention. Unlike traditional composting or open burning, which release harmful pollutants, pyrolysis offers a cleaner alternative. The resulting biochar not only improves crop yields but also locks carbon into the soil for centuries, making it a potent tool for climate mitigation.

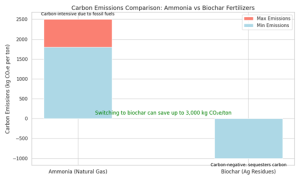

CARBON CUTS AND CLIMATE GAINS

The environmental dividends of biochar production are substantial. Life cycle assessments show that converting crop residues into biochar can reduce global warming potential by 10–24%, depending on the feedstock and energy inputs. This is achieved by avoiding methane and nitrous oxide emissions from decomposing biomass and by sequestering carbon in stable form. Moreover, substituting fossil-based fertilizers with biochar reduces the need for synthetic inputs, further curbing emissions. Forestry floor cuttings—typically left to decay—could also serve as feedstock, expanding the scope of carbon savings while reducing wildfire risks and improving forest health.

THE BUSINESS OF BIOCHAR

Economically, biochar is gaining traction as a marketable commodity. Its value lies in its multifunctionality: as a soil amendment, livestock feed additive, and even a component in building materials. Production costs vary with scale and technology—slow pyrolysis and microwave-assisted methods are particularly efficient. While small-scale operations may struggle with profitability, larger facilities benefit from economies of scale and co-product revenues from bio-oil and syngas. Governments are beginning to offer carbon credits and subsidies, nudging biochar into the mainstream of green investment portfolios.

Yet, the biochar supply chain is not without its thorns. Feedstock variability, transport logistics, and inconsistent quality standards pose challenges. Agricultural residues are bulky and seasonally available, complicating year-round operations. Centralised pyrolysis plants require reliable sourcing networks, while decentralized models face hurdles in technology deployment and market access. Certification schemes and digital traceability tools are being developed to streamline operations and reassure buyers of biochar’s provenance and efficacy.

A PILLAR OF THE CLEAN INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

Biochar is emblematic of the clean industrial revolution—a shift from extractive to regenerative systems. It exemplifies circular economy principles by transforming waste into value, reducing emissions, and restoring ecosystems. As industries seek low-carbon inputs and farmers grapple with soil degradation, biochar offers a rare win-win. Its integration into agriculture, construction, and energy sectors signals a broader reimagining of industrial processes.